Europe’s Misunderstood Problem with Youth Unemployment*

Rising youth unemployment in Europe has been a widely discussed issue over the last few years. Although millions of euros have been spent on youth employment programs, the result of these has been limited, to say the least.

One of the main reasons is the widely misunderstood statistical indicator “youth unemployment coefficient” itself. As a result of this, it is a common misconception that every fourth European aged 15-24 is unemployed.

When considering policies targeted at youth unemployment (especially among the most commonly mentioned 15-24 age group), we should account for the fact that the vast majority of people of this age are not considered a part of the labor force. This is completely natural since the larger number of people of this age is still at school, or at university.

The importance of this fact cannot be overlooked, since the number of people in the labor force is used when calculating unemployment levels. Youth unemployment rate is calculated in the same way as the one in other age groups – as a share of the unemployed of the total labor force.

However, according to Eurostat, only 5% of the 15-year-olds are considered a part of the labor force. At the same time, this is the case with more than 80% of the 24-year-olds. This peculiarity makes both measuring the youth unemployment rate and developing employment programs for such a heterogeneous group difficult, to say the least. The reason is that, because of the smaller denominator (i.e. the number of people considered part of the labor force), each young person that enters the labor market for the first time as unemployed, and each young person that loses a job and still seeks another one, have a greater impact on the unemployment rate coefficient than the unemployed people in other age groups.

Eurostat has a perfectly good explanation that few bother to look at:

“Because not every young person is in the labour market, the youth unemployment rate does not reflect the proportion of all young adults who are unemployed. Youth unemployment rates are frequently misinterpreted in this sense. A 25% youth unemployment rate does not mean that ’1 out of 4 young persons is unemployed’. This is a common fallacy. Also, the youth unemployment rate may be high even if the number of unemployed persons is limited. This may be the case when the young labour force (i.e. the rate’s denominator) is relatively small. This is not an issue for the unemployment rate of the whole population of working age due to the higher participation of that population in the labour market (43% at ages 15-24, compared to 85% at ages 25-54, 2012 EU-28 estimates)”

Once more – because of the smaller size of the workforce, every unemployed young person has a larger impact on the unemployment ratio than people in other age groups. This is the reason why Eurostat publishes one more (frequently overlooked) indicator – the youth unemployment ratio. This indicator shows the share of the unemployed in the total number of people in a given age group.

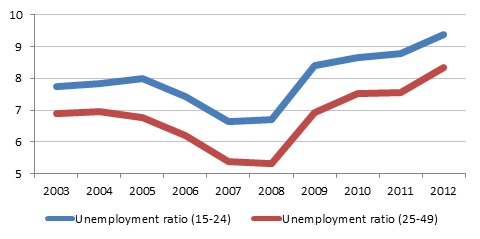

As it can be clearly seen on the graph, the dynamics of the unemployment ratio among people aged 15-24 is quite similar to that of other age groups, in this case the broader 25-49 age group, which includes a significant part of the total workforce.

Unemployment Ratios (2003-2012)

In other words, the high youth unemployment ratio is not an isolated phenomenon, but a consequence of the overall condition of EU labor markets, as well as the specifics of the age group itself.

Young people might be regarded as bright future prospects, but are hardly necessary when a company is in a „survival mode”. This is one of the reasons why in times of severe economic downturns they are most likely to lose their jobs as opposed to more experienced and skilled workers. They are also easier to convince when it comes to reducing working hours and payment, or engaging in different types of unregulated employment.

The lack of experience, skills and even professional contacts among young people, makes them understandably one of the more sensitive labor market groups. Trying to find your first job while companies are forced to let go even of the experienced workers is never easy. At the same time, some types of labor market legislation and practices (like collective bargaining agreements) make the dismissal of long-time employed, but arguably efficient, personnel in some European countries harder. These are jobs that young people could get and would get, if they were given the chance to compete with some of their less productive elders on fair terms.

These are all the things that have to be considered when solutions to the problem are offered. If the indicators that we base our policies on are not reliable or understood, there is no way to properly determine the effect of different policies. France might be pointed out as the negative example here, having spent millions on youth employment programs with no real effect on its youth unemployment rate.

How to make labor market entry easier

Deregulate internships. University education can only get you so far, and in the current circumstances young people are better off working for little or no pay, than staying at home. Overregulation and high costs to employers discourage internship programs.

Collective bargaining keeps inefficient workers employed and poses obstacles to the entry of young people into the labor market. Rising minimum wages leave low-skilled young people jobless. So does higher taxation.

Finally, it is all too clear that no politician will stand idly by and appear to do nothing when youth unemployment is so high. Still, it has to be understood once and for all that high youth unemployment rates are a function of deeper structural problems, inflexible labor markets and deteriorating economic and business conditions within quite a few member states. Patching up labor market issues rarely leads to significant improvement.

* This article first appeared in 4liberty.eu, October 15, 2013